It’s been almost three weeks since I completed Braking the Cycle 2012. Long enough for me to take my bike, The Blue Streak—her gears crunchy with grime and dirt, brake pads worn to the nubs after riding through rain for more than 100 miles, tires thinned and pocked with tears from flats—to the bike shop for a much-needed tune-up, new brakes, new tires. Long enough for a dozen more donations to come in. Long enough for the total mileage logged on The Blue Streak since I bought the bike to have exceeded 9,000 miles, a glorious bench mark I anticipated in my first blog post. But not long enough for me to write a postscript that will do my experience of the three days of the ride itself justice. This isn’t going to be that post.

Lost in the backwoods of hilly Connecticut, near the end of Day 2, after nearly 200 miles of riding. The thought bubble above my head would read, “Thank God, an oasis.” (On Braking the Cycle, a rest stop is called an oasis.) You can’t tell from my smile here, but I hate Gatorade. Photo by Alan Barnett Photography.

What I will say now is that the three-day ride was a microcosm of my whole, erratic summer: I rode as hard and fast as I ever have. I crawled uphill. I felt fantastic. I felt half-dead with exhaustion and everything hurt. I wept while pedaling. I sometimes had no idea if I could go on. I rode at the front of the pack. I caught a brief glimpse of the caboose, the two riders designated to be the tail end of the ride, chugging along behind everyone else. I was freezing and wet. I got windburn and was overheated. I discovered again that I am stronger and more tenacious than I realized—and that continues to surprise me. I forgot why riding 300 miles on a bicycle felt like a good idea. I forgot why doing anything besides riding my bicycle seemed like a good idea. I thought of every person I know, living or dead, who is affected by HIV. I thought of the recent wave of people I know who are my age and who have either died unexpectedly during the past year or who are braving and battling awful, progressive illnesses of all kinds, none of them HIV-related. I contemplated my mortality. I sang dumb pop songs, admired the foliage, inhaled the smell of autumn, and thought of nothing deep or nothing at all. I rode alone. I met and reconnected with old friends on the road. I made new friends on the road. I drank too much Gatorade. I drank too little Gatorade. I ate bananas, bananas, bananas. I found laughter in unexpected places. I was moved to tears by strangers. I was met with affection and cheerleading and applause at least once an hour, for just existing and showing up. I trusted the training. I doubted myself. I believed in myself. If one element was constant, it was only this: I kept going.

The more detailed blog-post summary of our civil rights march on two wheels, spanning three days across four states, will take me a little while longer to get around to writing, but in the interim I wanted to share some details about what happened when the ride was over because it deserves its own entry.

The check for nearly $221,000 that we presented to Housing Works at closing ceremonies, Sunday, September 30, 2012, 5:30pm. The actual final total will be higher, as riders and crew continue to fundraise until the end of October. Photo courtesy of Rich Biletta.

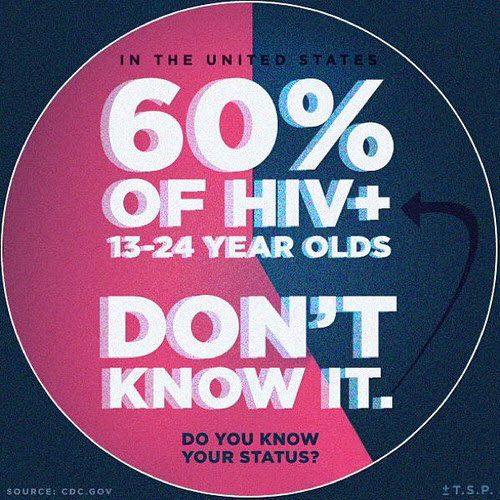

The first item of note is a series of numbers I’m joyful to share. By virtue of the subject matter of AIDS and HIV, most of the statistics I’ve referenced these past months have been unsettling, sad, infuriating. It’s therefore with a joyful heart that I can type this new figure for the books: As Sunday, September 30, 5:30pm, Braking the Cycle 2012 raised nearly $221,000 for Housing Works in the fight against HIV, AIDS, and homelessness. That amount has also been climbing rapidly in the weeks since, as post-ride donations continue to come in.

As of this writing, thanks to the financial support of the 134 generous souls who sponsored my personal ride efforts this year, and whose names are listed at the end of this post by way of acknowledgment and with all my gratitude, my portion of that handsome $221K+ sum totals $9,710. For those of you who work in sales or who like to see such totals framed against concrete, forecasting goals, $9,710 equals 129.5% of my final target goal of $7,500. I say “final target goal” because my original goal when I began fundraising in early July was $5,000. In mid-August, when the going was slow, I even had a panic-stricken week that I wouldn’t reach the $5K, no matter how many times I hit “refresh” on my First Giving website page every few hours. (O ye of little faith, Mika!) I was thrilled when I hit that $5,000 goal and was able to raise the target by 20%; I had no idea that I would end up raising it again twice more after that. So, needless to say, to have achieved a sum that is 194% of my original target goal has me astonished and approaching speechlessness.

The donations I received ranged in size from $20 to $725, and every bit counted and helped. These acts of kindness and support represent a diverse array of humanity residing in three different countries, including 18 states across the U.S. Contributions came from my closest friends and family, from colleagues, and even from people I’ve never laid eyes on. To each and every one of you who supported me throughout this challenge, and what proved to be a particularly difficult season, I could not have done it without you. Thank you again and again. You inspire me with your encouragement and with the expansiveness of your hearts. (And yes yes yes, if you’re reading this and thinking, “Damn, I meant to donate…” or “Wouldn’t $10,000 be a much nicer, rounder number as a total than $9,710…” or “To hell with that Fall Clearance sale, I think I’ll donate to Braking the Cycle and Housing Works a second time…”, the donation link is still up and running, and you can still kick in for another 7 days or so. For those of you who have had just about enough of my relentless BTC pitches and reminders, I know it may seem like the 15th Cher Farewell Tour—never quite over—but this really is last call for BTC 2012.) An additional thanks goes out to those who were unable to donate this year, but who have been continual cheerleaders and sources of love, inspiration, and encouragement, and who have expressed faith in me even when I didn’t have much in myself. You know who you are, and your generosity of spirit has kept me going all these months and all through the ride as well.

The second thing I’d like to share is a recap of the ride’s closing ceremonies, which took place at 5pm on Sunday, September 30, in front of Cylar House, a Housing Works facility on 9th Street near Avenue D, with the victory party following right afterward inside the building. Over the course of that afternoon, all the riders finished the last miles cycling through the Bronx and down the east side of Manhattan, to a holding area three blocks from Cylar House where we were gathered so all 90 or so of us we could ride to the ceremonies together and arrive as one big group, followed by the amazing volunteer crew.

Me, with speedy BTC rider Glenn Hammerson, gleeful after finishing the main ride route and arriving in the holding area three blocks from closing ceremonies, Sunday, September 30, around 4PM. Photo by Alan Barnett Photography.

Braking the Cycle riders gathering together in the holding area on East 12th Street, three blocks from Housing Works’ Cylar House, where closing ceremonies took place. This way, we get to ride in all together. Photo courtesy of Joseph Miceli-Magnone.

When I rolled in to Holding, I was relieved, thrilled, and excited on the one hand, but I also was nervous. About a week and a half earlier, rider coach Blake Strasser had emailed me to ask me if I would be one of the speakers during the ceremony. (The other speakers were Charles King, Housing Works President and CEO and BTC Rider #2; Eric Epstein, President of Global Impact, which has produced the Braking the Cycle ride since its inception a decade ago, and fellow BTC rider CB Kirby. Amazing jazz vocalist Thos Shipley also sang.) My first reaction to Blake’s request was to blush because I was flattered. My second reaction was, “You couldn’t get a gorgeous, articulate gay man who looks fresh as a daisy after cycling 300 miles to do it?” My third reaction was, “What? Margaret Cho wasn’t available?” My fourth reaction was abject terror and “?!*&#@.” My fifth reaction was to remember that at the closing ceremonies of my three previous Braking the Cycle rides, I was so exhausted, I could barely recall my own name. Those reactions took less than 30 seconds collectively, and then I wrote a reply email to Blake saying I’d do whatever she wanted, happily, and if speaking at closing was it, I’d be honored and privileged to do it.

Me with gorgeous Colby Smith, an incredible athlete (he did his first Ironman last month), in the holding area, post-ride, right before closing ceremonies. Yes, he always looks this good after riding 300 miles, and this was the kind of BTC runway model I was picturing as I contemplated who would make for a better closing ceremonies speaker than I. Colby is also a funny, smart, kind human being. Who *is* this guy? Photo courtesy of Colby Smith.

Over the next week, during which I did my last training ride and massive amounts of laundry to prep for the ride, I had just enough time for the reality of what I’d committed to doing to sink in. I had done presentations, lectures, discussions, speeches for groups of all sizes in all sorts of contexts before, but this one had me nervous. I’m never at my best when I’m sleep-deprived, and I also knew the moment would be too emotional for me to be able to wing it. I also wanted to try to say something that would resonate with all the audiences who might be there—the riders and crew, also exhausted and elated; all their families and friends, including many people who had donated to the ride; Housing Works staff; and Housing Works clients, past and present—something that wasn’t canned. I spent a week thinking about it, and the week of the ride, I drafted it on Tuesday night, I had Jen read it and edit it on Wednesday, I sent the mostly final version to Blake on Thursday, the day we drove up to Boston for ride orientation, and I practiced it a few times during the lulls that day. Thursday night, I gave a spare copy to Jen to hang onto as a back-up, and I folded my copy into a Ziplock bag to protect it. That plastic bag stayed with my baggage for my first two days (and 200 miles) of riding, and then went into my cycling jersey pocket at 4am on Sunday morning before I peeled out of Bridgeport, Connecticut, with my fellow riders at 6:30. And with me it stayed for 85+ miles until we arrived at Housing Works in the East Village.

The 85 or so miles of riding that day were challenging enough to keep my mind off the speech. But my anxiety came back in a rush during that extended period of hanging around in the holding area, hugging other riders as they arrived, drinking coffee to wake and warm myself up, taking bad candid pictures with ultra-photogenic, attractive people, texting friends who had left messages. I would momentarily forget about it while congratulating another rider, and then some part of me would seize up with the memory that I was going to have to Pay Attention and make sense. Dear God, I had to talk? In front of other people? About something that mattered? What had I been thinking?

Woot woot! Me on Day 3 in New York City, finishing the official ride route as I pulled into the holding area on East 12th Street. My nerves about having to talk at closing ceremonies kicked in about 15 minutes after this was taken. Photo by Alan Barnett Photography.

I must have been jacked up enough with nerves that what followed after I gave the speech is even more of an adrenaline blur than the ceremonies of previous BTC rides. And possibly because this was my fourth Braking the Cycle ride and no longer the novelty that it once was to those who know me, I was amazed by all the people I knew who showed up to greet us and me, how warm they were, how touched I was to see their smiling faces, to get a hug from each of them. The people who are the biggest, most personal reasons I do this ride were standing right up front. One close friend and training buddy brought me an entire box of cupcakes. Another had driven up to East Lyme, Connecticut, to cheer me, and all of us, up the dreaded Mount Archer on Day 2 of the ride, and he was there again at closing ceremonies, cheering and helping with bike check-in and storage. Dear friends who were previous BTC riders and crew were there, too, whooping and hooting. My parents came and surprised me by bringing my brother, who lives out of town. A number of friends surprised me, too. One who I wish I saw more often came, and when I said, “I had no idea you’d come,” he smiled sweetly and said, “Of course I came.” My oldest childhood friend didn’t tell me she was coming at all, and then surprised me by showing up. Two of my closest friends from work came; they are each far more than what we usually deem as work friends—to me they are simply friends in the truest sense, and the work link is secondary and largely incidental—and yet because office-based connections come with their own peculiar social oddities, formalities, and awkwardness, I was especially surprised and moved to see them.

With fellow riders (Chad Woodard and Matt Martin to my left, Rodney Newby to my right) on Avenue D, about to turn the corner onto East 9th Street where a big crowd of applauding friends, family, and other supporters awaited us. It is a mystery what I might have swallowed to produce the beautiful expression on my face. Photo courtesy of Roger Lovejoy.

But when we first rode down East 9th Street, I didn’t see anyone I knew well. All I saw was a massive crowd of people, which in that initial moment, moved me instead of scaring me. It had been threatening to rain all afternoon—we had been doused by a brief shower when we cycled through Harlem earlier—it was chilly, and yet these loyal, tender-hearted people were standing, waiting, cheering, for us. I had been told to position myself near the stage, and when I got there, I had barely dismounted when I noticed several middle-aged African-American women approaching me and the riders immediately around me. We didn’t know them. They were strangers, and yet the second they saw us, their faces lit up and brimmed with emotion, and they moved toward us with outstretched arms. Without even consciously thinking it, I understood they were Housing Works clients. The one nearest me hugged my shoulder, kissed my cheek, and over the din of the crowd’s applause and cheering, she murmured in my ear what I am certain the other women were saying to the riders they were embracing: “Thank you. Thank you so much.” They didn’t have to explain further. It was in their voices. It was evident in the way a stranger wrapped herself around me without hesitation.

One of the women who first greeted all the Braking the Cycle riders as we arrived at closing ceremonies. I believe this was taken at some point during my brief speech a few minutes later. Photo by Alan Barnett Photography.

With that gratitude ringing in my ear, my heart swelled. As for my anxieties, they didn’t disappear; they just ceased to matter. The energy from everyone there was what was thrumming around me and in me when Eric made his introductions and I heard him call my name to prompt me to come up to the stage. I took in that none of the stage set-up was great. The sound system was iffy. The mic didn’t have a mic stand, so I had to hold the mic with one hand while I propped the pages of my speech up against the podium with the other. My hair, ever frizzy in rainy weather, kept whipping about and getting caught on the mic. The wind picked up and flapped at the pages of my speech. None of it mattered. I took a deep breath, I talked for a few minutes, and the crowd of people in front of me listened, and clapped, and listened some more. People clapped afterward and said nice things. We went to the victory party, where I hugged and chatted with some friends more; I ate a cupcake and drank the best beer I drink all year; and Jen and I cabbed it home with my bike in tow. Since then, some folks have expressed curiosity about the speech, so I have pasted the written manuscript below. Minus, of course, the spontaneous ad-libbing I did onstage, this is what I said:

Me, talking at Braking the Cycle’s closing ceremonies, Sunday, September 30, around 5:30 PM, with rain looming but thankfully not materializing. In front of Housing Works’ Cylar House facility, 9th Street and Avenue D, New York City. If I sort of give off the air that I’ve just gotten off my bike after riding 300 miles, it’s because I have. Photo courtesy of Kate Asson.

Braking the Cycle Closing Ceremonies Speech

Cylar House, Housing Works, New York City, September 30, 2012

There’s a homeless woman who has frequented my Brooklyn neighborhood for all 12 of the years I’ve lived there. My partner Jennifer and I call her The Quarter Lady because when she asks for help, she always asks for a quarter. She tends to make people uncomfortable—because while it’s not clear what’s wrong with her, it’s clear she isn’t all there. The only things she says that are easy to make out are “Miss, you gotta quarter?” and “thank you.” She can be a little scary, possibly unstable, suffering from withdrawal, physically ill, mentally ill—maybe all those things.

For years, I gave her money when I saw her. When months went by and I didn’t see her, I’d worry a little, and hope nothing terrible had happened to her. When I saw her again, I’d be relieved and vaguely deflated—glad to see her, but sad that she was in the same place. Time seemed to stand still with the Quarter Lady. Everything always the same.

Then one day, something changed. Instead of being on her usual corner, she was on a side street, sitting on the stoop of a brownstone. She may have asked me for a quarter. I said something to her about the weather. And in the very next moment, the Quarter Lady suddenly became grounded. Her lucidity, which I’d never seen before, was visible. The first thing she said, I’d heard from her many times—which was “thank you.” Then she gave me a penetrating, compassionate stare that felt like she had peered in at the very core of my self and seen the entirety of my soul, my strengths, my flaws, all of it. And she said, “Someday I hope I’ll be able to help you too.”

I’m not sure what I said. Possibly thank you, and that I’d like that. I was on the verge of tears and I didn’t know why. We waved goodbye, and the next time we were back to our usual exchange about quarters.

I had so many obvious advantages, necessities, and privileges—a home, a job with a salary, my health, health insurance, a loving partner, family and friends. But inside, I was having a hard time that year. I was depressed about various aspects of my life, and I felt lost a lot of the time. And that morning, a virtual stranger who wasn’t even all there most of the time had seen me for exactly who and where I was in that moment, recognized I was in pain, and said something kind.

I was 9 years old when the first cases of AIDS were reported.

I was 10 or 11 when they finally figured out that sex was the major mode of HIV transmission.

I was 15 when the first person I knew who was HIV+ got sick and then quickly died of AIDS, a close friend of my mom’s. He wasn’t out as a gay man, he wasn’t out with his HIV status. When he died, his obit said he died of cancer. That was in 1987.

I was 31 when my brother’s friend Curtis died of AIDS. Curtis was out and outspoken about everything—about his love for art, about being gay, about being HIV+ and battling AIDS. Eventually his body lost the battle, and he died in 2003.

I’ll be 40 this year. Like so many people here, probably everyone here, AIDS has been a shadow part of my life for over 30 years. I know more people who have died from it. I know people who found out they were HIV positive last year. I also know more people who are living with HIV than I can possibly name here. The good news about that last category is that they are the lucky ones: They know that they have it, they treat it, and they manage it. They’re lucky to have survived what so many of us call the years without hope before 1995 when antiretrovirals got better and became more available, and that they had access to the right services and resources.

Without movement and change, healing isn’t possible. I don’t know whether The Quarter Lady has HIV or any other illness. I know that she moved me because for a few brief minutes, she reminded me that so long as we’re alive, we all have the capacity to change and in turn, heal ourselves and one another—no matter how difficult our circumstances, no matter how unlikely it may seem, no matter how hard the journey to make that shift. It doesn’t matter whether the Quarter Lady ever helps me in some material, visible way. She helped me by imagining a different future in which she was helping me because I was in need rather than the other way around.

Since its founding, Housing Works has advocated for people at the margins who have been given up for lost, who have been considered to be beyond help, beyond change, beyond healing, long before they die a physical death from AIDS. Housing Works has gone where other groups wouldn’t go—they acknowledge the connection between poverty, homelessness, AIDS, HIV testing, treatment, addiction, IV drug use; they recognize them as interrelated; and they create a space without judgment where second chances are authentic. They imagine other ways things might work, and they make change. In making change, they facilitate healing. It’s no accident that the people who start off as clients come back as activists and advocates and staff members when they’re back on their own two feet.

People ask me all the time why I keep doing this ride. I do it because I have friends who live with HIV and because I’m all too aware of the fact that it could easily have been me. For me this ride has functioned a lot like Housing Works has for many people. Being part of this ride has helped me challenge myself and go far beyond what I thought I could do in the world; it helps me find change within myself. I ride because the people I’ve met along the way inspire me. They show up even when it looks like there isn’t any more progress that can be made. I didn’t know until pretty recently how much healing the experience of being part of this would offer me.

By being here today, whether you’re a rider, a crew member, a Housing Works client or staffer, or one of the many, many kind people here who support this cause and this community—with time, with money, with compassion—you’re a part of that healing process, too. I know for a fact that your engagement with this community, with this issue, has been source of healing for someone else, probably someone else who’s here today. And until the final end to this terrible pandemic: I hope that being part of this fight helps you find a measure of healing as well. Thank you.

Mika’s Braking the Cycle 2012 Rock Stars

*= donor to previous Braking the Cycle AIDS ride(s)

- Anonymous (1, 2*, 3, 4*, 5, 6, 7*, 8*, 9*, 10*, 11*, 12*, 13, 14*, 15, 16*)

- Beth Ammerman*

- James Anderson & Suzy Turner*

- Jennifer Anderson*

- Renee Anderson*

- Chris & Mel*

- Catherine Angiel & Team

- Janis & Dave*

- Leah Bassoff*

- Charlie Baxter*

- Jon Bierman*

- William Bish*

- Penina

- Buddha Tara*

- Meghan Campbell

- Steph & Bill Carpenter*

- Lynne Carstarphen

- Danielle Christensen

- Jane & Tony*

- Clare Cashen

- David Chodoff

- Terry Christopher

- Marcia Cohen*

- Barbara Conrey*

- Katie Crouch

- Kevin Colleary

- Susan Conceicao*

- Barbara Conrey*

- Rich D’Amico & Mike Meyerowitz

- Carol Diuguid

- Annie & Jon*

- Carey

- Timothy “San Diego Cupcake” Fitzpatrick

- Ray Flavion*

- Suzie & Bernadette

- Kory Floyd

- The Food Healer*

- Kerri Fox

- Svenja & David*

- Michael Gillespie*

- Christina Gimlin

- Dawn Groundwater*

- Amanda Guinzberg *

- Myles

- Scott H.

- Karen Henry*

- Jess Holmes

- Nancy Huebner

- Tom Hyry*

- Andrea Vaughn Johnson & Eric Johnson*

- Angela Kao*

- Katie K.

- Cara Labell

- Elena Mackawgy

- Matt & Jessica*

- Carolyn Plum Marshall

- Paul & Luke McDonough

- Derek McNally

- Dave Meier*

- Lorraina & Ben Morrison*

- Lai & Greg*

- Elizabeth Murphy

- Liz O.

- Jacob Okada*

- Eva & Tom Okada*

- Gregg Passin

- David

- Nancy Perry*

- Lisa Pinto*

- Eileen*

- Briana Porco

- Gabriel Presler

- Josie Raney*

- Cory

- Sarah R.

- Rhona Robbin*

- Greg Romer

- Mike Ryan

- Carla Samodulski*

- Terri Schiesl

- Sigrid Schmalzer*

- Roger Schwartz*

- Brian Seastone

- Brigid*

- Jane Smith*

- Janet Byrne Smith

- Fred Speers & Chase Skipper*

- Lynn Stanley*

- Matt & Jen*

- Danielle & Arturo*

- Kelly Villella*

- Jasna & Paul

- Clay & David

- Sherry Wolfe*

- Yu Wong*