It is 5:40pm on Saturday, November 3. The worst of Hurricane Sandy has been over for five days. Jen and I just got home from walking to the southern part of Red Hook in Brooklyn, where the post-storm devastation is ongoing.

We didn’t stay home during the storm. We spent the days of the hurricane with generous friends who live inland in Brooklyn, two neighborhoods away. The rear side of our apartment building faces west and is on the eastern side of Columbia Street, a narrow, two-lane street that runs parallel to the waterfront. Prior to Hurricane Irene last August, a close look at the city’s hurricane zone street maps revealed that this location places us exactly on the border of an evacuation zone. Everything north, west, and south of the west side of Columbia Street is designated as part of the mandatory hurricane evacuation area—and with good reason. It is one block from the water. The only street located west of Columbia in our little part of the neighborhood is Van Brunt Street, which runs parallel to Columbia and overlooks the commercials piers and stevedores that dot the south Brooklyn waterfront.

In the Google map I created below, our section of the neighborhood—distinct from the more gentrified Carroll Gardens because it is located west of the Brooklyn Queens Expressway, and only accessible by four overpasses and one pedestrian footbridge going over the highway—is marked in green. The dark red line marks the division between where we live and the red mandatory evac zone to the west. Our little green plot is technically the northern section of Red Hook, but because it is just north of the Brooklyn side of the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel and Hamilton Avenue, a commercial thoroughfare that runs directly underneath the BQE (Route 278 on the map), it is also cut off from the main part of Red Hook. On the map, Hamilton is denoted by the diagonal lavender line, and the primary parts of Red Hook, all part of the mandatory evac zone, are to the left of that line, marked in red.

I like maps, but I also understand them well enough to know that many of their borders are artificial; just because a map says we live, just barely, on the advantageous side of an evacuation line doesn’t guarantee a hurricane will pay any attention to that particular distinction and stay on its side of the divide. In addition, the two drains in our building courtyard are partial to flooding during thunderstorms, and we live on the first floor. That being the case, both last year during Irene and this past week during Sandy, we decided to be on the safe side and move inland because we could. We spent from Sunday to Tuesday evening safe and dry, six flights up in downtown Brooklyn. By Monday morning, long before the landfall and the worst of the storm, we were seeing photos from the southern part of Red Hook that looked like the one below, which was taken by a local resident from the southern-most end of Van Brunt, where the Fairway supermarket is located. Our building is a 15-minute walk or a three- to five-minute bike ride from where this snapshot was taken, so we had no idea what to expect when we finally returned home.

A now infamous image of flooding in southern Red Hook, Brooklyn, the morning of Oct. 29, 2012, from the southern-most end of Van Brunt Street near the Fairway supermarket. Photo by Nick Cope/Green Painting

In the past three days, I’ve said, emailed, and texted—more times than I can count—that we were very lucky. Our little stretch of Columbia Street was spared. Amazingly so. No flooding. No power outage. Our minor difficulties have all been inconveniences rather than genuine, serious problems. The lack of any viable transportation to Manhattan has kept us at home. The cable has gone out periodically, our internet signal was out entirely until this afternoon, and phone service all over the neighborhood has been and remains spotty at best. All week, I sent and received email sporadically via a weak and equally spotty 3G signal. Texting has proved to be the most reliable communication channel—even though it takes three to six failed attempts before any message goes through and incoming messages often don’t show up for hours if at all.

We spent most of Wednesday at home; I don’t think we realized how stressed out we were about what might be happening to our apartment until we got back. On Thursday morning, my work laptop and I headed to Maybelle’s, the one local coffee house with both wifi and electrical outlets for three-prong computer plugs. The small place was mobbed all day and freezing, but I spent most of the day there anyway, grateful that I had anywhere to go where I could attempt to get some work done. On Friday, we were out of luck again in trying to find an online hook-up; Jen trotted off to Maybelle’s in the morning only to return a while later saying their wifi signal was kaput.

These are all good problems to be having. When we were still at our friends’ house on Tuesday morning, our friend and neighbor Andi, whose building two blocks from ours had also held up fine, relayed to us via text that everything south of Hamilton Avenue and the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, just a five-minute walk from us, was a mess. “…Red Hook looks pretty bad,” she reported. “Power out there, bad flooding, gas/oil/chemicals on the sidewalks.” The photos that have been posting online in the days since then have confirmed that description and documented worse.

We didn’t doubt that the damage was severe. When I went to the bodega next door on Wednesday afternoon to pick up milk, the owner, Mrs. Li, asked, in her halting English, after me and Jen. As we were talking about the storm, she told me about a customer from that morning who lived on Staten Island. The winds were so strong that the woman’s brand-new outdoor fence was carried away hours before the main part of the storm hit. The surge that followed was so encompassing, boats from the marina smashed into floating cars and drifted into her yard. The flood level in her house was soon so high, she and her family had to swim out to safety.

Hearing a harrowing story like that made it all the more strange to be walking around Carroll Gardens, where everything was mostly the usual. Aside from the huge, downed trees and the shelves at local stores that are low on stock if not entirely out of certain key items—batteries, flashlights, bottled water, candles—the signs of damage and storm impact are minimal. Even on our grittier side of the highway, although the streets are quieter than usual and many of the local businesses remain closed, you wouldn’t know from appearances how truly lucky we are. The only visual signs that something is amiss are increased bicycle traffic and long lines at the grocery stores, bakeries, and restaurants that are open. The view from our bedroom window facing the street doesn’t show how close we are to staggering losses, places where people are still living under terrible, near-unimaginable conditions that show no signs of dramatically improving any time soon.

Like a lot of locals, we thought it was important, essential really, to show our gratitude for how unscathed we are by trying to offer some help to our neighbors. As Jen put it to me last night, “I was scared for us. For our home. For what could have happened to everything we own. I don’t think I could show my face in the neighborhood if we didn’t do something to try to help the people down the street.” Jen has been following the Twitter feed of the Red Hook Initiative (RHI), a local community center that offers a range of health, education, employment, and neighborhood development program. In the wake of the storm, RHI is redirecting all its efforts and resources toward hurricane recovery work, becoming a de facto focal point for relief efforts and support, so that’s where we headed. The Twitter updates have offered up useful information about the kind of volunteer work that is available, about the kinds of supplies and help that are most needed, all in real time.

Our first stop was the Met Food on Henry Street in Carroll Gardens. On our way there, we passed by Maybelle’s again. Crystal, a student who we know because she’s worked part-time at various cafes in the neighborhood, was sitting on the bench out front having a cigarette, so we stopped to chat and ask her how she was. “Your expression looked so serious,” remarked Jen, “I almost didn’t recognize you.” Crystal works in and around Carroll Gardens, and her mom lives there, but Crystal herself lives with her aunt and uncle on Staten Island. She’s spent the past few days shuttling between her mom’s and trying to repair the severe damage back in her own neighborhood, where many people have lost their homes altogether. Those who haven’t are still waist deep in flood water, with no running water or heat, and the only people with electricity are those with generators. Crystal described trying to drive through there at night to pick up salvageable clothes and supplies. “It’s pitch black, no light at all except from the headlights of my car. It looks like the zombie apocalypse.” She told us she’s been pretty freaked out, and today was the first day she could even talk about it without choking up. But she also noted that nearly everyone has been resilient and helpful. “We wouldn’t have any power at all at my house if our neighbors didn’t have a generator that they loaned to us. I bought a bunch of blow-up air mattresses, and I’m telling friends they can crash at my house for as long as they need to. We’re all doing what we can and what we gotta do. Last night,” she said, pausing to grin in a mixture of what looked like self-consciousness, shyness, and pride, “we made twenty pounds of pasta and then spent all night serving dinner to anyone who needed to eat.”

After hearing that, suddenly our trip that afternoon became more real, more urgent, more sober. Jen had a list of supplies that were atop the RHI want list for the afternoon, and first at Met Food on Henry Street and then at Winn Discount on Court Street, we filled our granny cart with as much as we could find. It sounded like a lot of people were already bringing in bottled water and food that won’t spoil easily and doesn’t require cooking, so we focused on the other miscellaneous things one wouldn’t necessarily think about under normal circumstances: dry dog and cat food, maxi pads, diapers, mops, replacement mop heads, rubber gloves, sponges, bleach and other cleaning supplies, industrial-strength garbage bags, buckets, batteries, flashlights, candles, matches.

RHI is located on the corner of Hicks and 9th Streets in the heart of Red Hook. It’s mere blocks away from the NYCHA Red Hook Houses, the biggest public housing project in Brooklyn, with between 5,000 and 6,000 residents, and also among the poorest and most dangerous and crime-ridden. Because Met Food and Winn Discount, both located in Carroll Gardens east and north of our apartment, were the best places to stop and get cleaning supplies, we took a more indirect route to get to RHI than we might have, had we gone straight from home. After leaving Winn Discount, we walked south on Court Street, Jen pushing the heavy shopping cart, and then we took a right at 9th Street, crossed the treacherous, heavily trafficked Hamilton Avenue, and continued heading back west down 9th until we reached Hicks Street. We passed by the Red Hook shelter on the way, and the lines of people waiting outside to see if they could get a place to stay for the night were four and five people deep and extended all the way down the block in both directions.

We hadn’t been to RHI before, but we didn’t have to look at the street signs to find it. The crowds of people, the flash of emergency lights from police cars, and the cluster of double- and triple-parked vehicles told us. Volunteers were unloading cars and vans full of aluminum trays of food, pallets of water and paper towels, blankets, and clothing. Inside, through the windows, I could see an elaborate assembly line set up for feeding people, and the line of hungry locals waiting to get a meal snaked out the door. Supplies were in such high demand, most weren’t even making it into the facility. They were being organized by category by the wall outside, so people could drop donations off quickly and others could easily locate and pick up what they needed. Everyone was carrying something, bags laden with food, shopping carts, backpacks, and they were all moving quickly, trying to make it to safety, wherever that might be, before the sun went down and the neighborhood became pitch-black again.

It was a sobering sight. A far cry from Maybelle’s and Carroll Gardens, where some of the local kids had been able to go trick-or-treating on Halloween. Once our cart was empty, Jen and I kept walking west on 9th Street, where two blocks later, another clog of people and city buses being used to transport resources was clustered in front of a Catholic church that was also offering recovery assistance. We didn’t say anything to one another as we walked along. There wasn’t anything to say. The air was clammy and cold. The sky looked strange, sunny and piercingly blue in some stretches, and in others, swollen and claustrophobic, heavy with menacing, low-hanging clouds shaped like giant tunnels. We took a quick right onto Columbia Street, and a left at Verona Street, which runs along the northern edge of Coffey Park. Earlier in the day, people had been distributing food and water there, but now that nightfall was only a few hours away, the park was empty, littered with fluttering, yellow police tape and massive downed trees. We stayed on Verona until we hit Van Brunt, which is the main drag and which offers the quickest access back north, across Hamilton Avenue and to our side of the neighborhood. It’s also the primary part of the regular route we take on weekends when we walk Sadie down to Louis Valentino Pier, a park beautiful park overlooking the harbor, with the Statue of Liberty in the distance.

I’m not sure what we expected as we walked up Van Brunt. Because we had accomplished our small mission, because five full days had passed since the worst of the hurricane had subsided, because that particular spot is only four blocks south of Hamilton Avenue, some six or seven from my house, some part of me must have thought, hoped really, that what we were to encounter there would be an improvement, well on its way to being back to normal. I had heard about and anticipated the waterlogged debris and garbage sagging in clumps on street corners and on curbs, pools of gas and oil on the sidewalks. I didn’t expect the steady stream of runoff water tricking along the street gutters, not from street flooding, but rather from all the water still being pumped or carried out of the surrounding houses and properties. I didn’t expect to find our friend Danielle, surveying her demolished front yard, sorting through her waterlogged, mostly ruined belongings, fielding calls from her kids, who have been spending their nights at friends’ houses.

We don’t hang out socially with Danielle and her husband, but we have known them and been their clients and neighbors for many years. They own the local dog and cat daycare place, just a block from our house; they do dog-walks, too, and they have cared for our dog Sadie for over a decade. Their business space, located on our side of the highway, was, like our building, spared: no flooding, all the animals were safe, and they were open for business again by Wednesday. Because Jen and I didn’t know whether we would or wouldn’t be able to go into work each day this week, we’d exchanged emails with Danielle each day, first with her letting us know when everything was fine and up and running at her end and then confirming whether we needed to have Sadie walked. Those exchanges were so business-focused, and so stoic, we had no idea until we walked by this afternoon that Danielle’s house, located just five minutes away from our house, had been pummeled by the storm.

That Danielle and her family still have no power isn’t surprising. No one on that side of the highway does right now. But the only source of heat is a makeshift wood fire she and her husband built on a barbecue grill. When we walked by, the grill was positioned at the foot of their front steps, and an elderly person we didn’t recognize, presumably a neighbor, was sitting on the stoop in front of the grill to keep warm. Most startling of all was the noise, the buzzing and rattling of an enormous electric pump, with one hose leading into the basement to siphon the water out and another pipe extending out the front yard, which was still belching flood water out of the house and into the street. Danielle’s house is two stories, plus a basement. The hurricane water surge filled her entire basement, floor to ceiling, and the first floor where they live was filled with nearly two feet of water. A fog of confusion drifted over Danielle’s face as she tried to describe the peculiar flood path of ordinary household items. The heavy, plastic container full of dog kibble that floated and drifted into another room. Her Christmas ornaments that ended up on the lawn, where she later caught a stranger looting through her soggy stuff, rooting through holiday decorations to steal the ones she wanted.

We tried to offer her help if she needs it in the coming weeks. Clean-up help, baby-sitting, somewhere for her kids to crash, a place to do laundry, an hour or two away from the mess to have a drink, take a nap, soak in a warm bath. For the moment, all we did was take in her pet love bird. The bird had been moved from Danielle’s house to the business space for safety reasons, but Danielle noted that the bird was probably unhappy there, from lack of attention and an overdose of barking and whining from the menagerie of other animals. So we picked up Izzy on our way home, and she’s chirping away in our office as I type this.

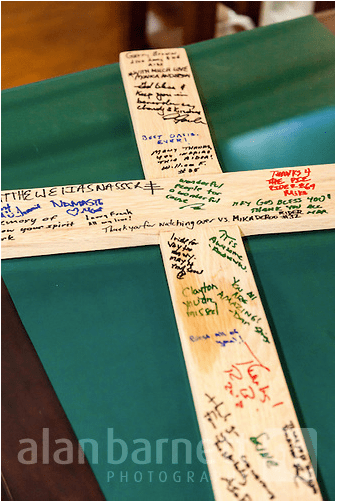

Aside from the Google map I annotated to give readers unfamiliar with the area a sense of its geography and scale, and the already widely posted photo of Red Hook flooding that went viral on Monday morning, I intentionally decided not to post any other images of the wreckage or the poignant, unsettling relief efforts. A ton of grim photos online mirror elements of the narrative I’ve tried to relay here—and these startling images have their place in helping to show how dire things are in certain parts of the city and how much help is needed and where—but I am not a neutral journalist, conveying news objectively. I decided not to re-post those pictures for the same reason I didn’t take any photographs when I was walking through the neighborhood myself. It’s the same reason that it gave me the willies to see how visitors flocked to stare at and take their pictures in front of the 9/11 site while it was still a smoldering crater of dust and debris in the ground. Because the act of doing so, as someone who isn’t either a resident or a journalist, would have felt distancing, dehumanizing, and voyeuristic, like I’m some sort of disaster tourist coming to visit other people’s misfortune and suffering and observe it from afar like it’s a safari or an exotic Survivor-esque museum. It’s not a diorama. It’s not a made-for-TV disaster film. It’s not yet history. It’s real, daily life for flesh-and-blood people, many of whom don’t know when or where they’ll get their next warm, home-cooked meal or if they’ll have a dry, safe, heated place to sleep tomorrow night.

Likewise, I am not writing about any of this because of a lurid fascination with catastrophe sites. Or because it makes a good dramatic story. Or because I think it’s newsworthy that we spent a few hours helping out in our own neighborhood. In fact, none of this is about me or Jen or our family, except that it’s no more than mere chance that we’re fine, and Danielle and her family and lots of other neighbors are not.

This is why I’m writing: The hurricane will soon become old news in the media, especially once all the subways are up and running again, and most people, myself included, are able to get to work on Monday. It won’t be old news for Danielle or my other neighbors on that side of the neighbor hood. Those damaged sections of Red Hook may not have power again until at least November 11. No running water, no electricity, no heat, virtually no transportation, no fuel, and uneven, limited access to food, potable water, and supplies. The lack of power also means that all recovery work needs to take place during daylight hours, even as the days are getting shorter. I’m certain other similarly devastated areas are facing comparable challenges.

I am writing about all this because based only on the little I’ve seen, and I have seen very little of the worst pieces of what’s happening out there, I can say firsthand that the storm damage is deep, wide-ranging, and long-term. Help is needed now, a lot of it, and it’s going to continue to be need for weeks and months to come. And it’s pretty easy for most of us to help because there are a ton of places where people can do whatever is within their means, as well as a range of ways to contribute.

Please: If you are able, go find a way to help that works for you and do something. If you have time to volunteer, go spend a few hours helping with clean-up, or shelter efforts, or distributing food, water, and supplies at one of the relief centers. If you don’t have time, but have material goods you can either donate, or purchase and then donate, go online and look up what’s needed where, and give some clothing, food, water, cleaning supplies, toiletries, etc. If you’re unable to give time or donate supplies, and/or you’re too geographically removed from any of the disaster sites to be able to help physically, donating money is an equally helpful option. Every little bit counts. The point is that we all should do something if we can—because we can. At the end of this post, I’ve included some links to a handful of place where you can start exploring help options, but a simple Google search and scanning of news articles about the storm aftermath will yield more as well.

In addition, please expand the support network by re-posting information and links to available volunteer and donation options anywhere and everywhere: Facebook, Twitter, email.

Ways You Can Help

Because the national efforts via government agencies and large relief organizations like the Red Cross are already widely publicized in the press, and because they are farther removed from the actual sites needing help and it may take them longer to get their resources to where they need to be, the initiatives listed below focus more on localized, on-the-ground efforts:

Red Hook Initiative: http://www.rhicenter.org/.

Red Hook NYC Recovers: https://redhook.recovers.org/, an online resource coordinated by the folks at OWS and community organizations on the ground that was built to enable people to both offer and request assistance. Sites for donations and volunteering have been set up in multiple locations, some in Red Hook, but also in other areas like Sunset Park, the Rockaways, and Staten Island.

CityMeals-on-wheels: https://www.citymeals.org/, an organization whose mission is devoted to getting food and human company to home-bound elderly New Yorkers. This is one of the most vulnerable and least visible populations affected by the hurricane, especially elderly people living in high-rises that have lost functional elevators and power. Here is a great overview on the emergency services CityMeals is providing: a release on the CityMeals website about their post-hurricane response.

For tomorrow, Sunday, November 4. NYC Marathon of Relief Efforts (NYC MORE 2012): www.nycmore2012.org, a group of runners and volunteers who have turned the cancellation of the NYC Marathon into an all-day volunteer opportunity, with options to volunteer in the Rockaways, Staten Island, and Coney Island. Also includes ways to donate goods and funds.

Occupy Sandy Relief: http://interoccupy.net/occupysandy/, another online resource built by a coalition of people Occupy Wall Street, 350.org, recovers.org and interoccupy.net. Its offering are similar to Red Hook NYC Recovers, but its information is on facilities serving other affected areas, not just Red Hook. Includes volunteer and drop-off locations in Chinatown, the Lower East Side, Rockaway, Coney Island; drop-off-only locations in numerous locations in Manhattan, Queens, and Brooklyn; and a portal to help in New Jersey.