It’s been weeks since I wrote a post focused on my actual physical training. Despite my blogosphere silence, I have been diligently putting in weekend miles the past month, and I’ve been riding to work when I can as well.

It’s telling that I wince at the thought of admitting to physical training challenges. And humbling. It has been, and remains, an uneven, tough season. The causes are the predictable ones:

- I started late. My riding season began in April, but the methodical, bulldog-like, and progressive training that I fall into when I have an event on the horizon began later than usual this year, in early July.

- We traveled in June, which is atypical, and I didn’t ride much for the first half of the month.

- I’ve been busy with work and life and out-of-town visitors, too, and my night-owlish tendencies have been worse than usual.

- The erratic, hot weather hasn’t helped. Our air conditioner usually stays in storage until mid-July; this summer, it was going full blast before mid-June.

I didn’t think much of it at first that my riding wasn’t feeling strong most weekends in July. In previous years, I’ve experienced some kind of boost in June or by mid-July, rides during which the time and effort I’ve been putting in kicks in visibly—faster average speeds, better stamina, stronger performances on hills. Sometimes, it’s been as amorphous as feeling fantastic and fearless while riding, as though I could ride on for hours even if it is 100 degrees out.

Nothing like that happened this season. I haven’t been putting in the miles and time consistently as I had in past years, and I figured that was catching up with me. The hills felt harder. The heat felt hotter. It all felt harder. I assumed I knew all the reasons why.

The above reasons have been playing their part, no question. But the past month, a new, unexpected factor emerged: mild, intermittent asthma.

An advantage of riding the same route frequently is that I have a good sense of my performance at various, specific geographic points on a given day. On a strong day, I might be able to take a certain stretch of road at 18 mph instead of 16 mph. Or I can eat a hill like it’s a delicious breakfast one week, but the next, I feel like I’m the martyred Robert De Niro character from The Mission, dragging myself up a cliff while weighted down with heavy metal weaponry, slipping every few steps.

Robert De Niro as Rodrigo Mendoza, The Mission (1986). Mendoza schleps a net full of metal weaponry up the cliffs of Iguazu Falls. On difficult days, of which there have been many, this is what training has felt like this season.

On July 22, when I rode on a Sunday after taking the previous day off, I felt okay but not great. Slow. Easily winded. Hot. Nothing dramatic happened, but I noticed I was dragging a little. My pace on hills wasn’t great. I didn’t feel right. My chest felt a twinge tight. I had a slight cough and a tickle in my throat. I figured I had picked up a low-grade version of the virus floating around my office.

That week, I continued to feel iffy, more tired than usual, but then again, so did everyone else. It was a hazy and soupy July. No one on the streets or the subway or in my office looked energetic. They looked put upon. I was still bothered by an intermittent barking cough. Stranger still, my chest stayed tight. A few times during the nights that week, I was awoken by something that was halfway between a cough and a choking episode, as though I had swallowed water the wrong way in a dream and woken up in the middle of it.

The following Saturday was much the same as the previous one, except that it was humid as well as hot, and the uneasy feeling I had while riding the previous week kicked in again full force. I was meeting my friend Terry, who lives in New Jersey, we meet at the southern entrance of Palisades Park. It’s roughly 15 miles between my Brooklyn apartment and the park entrance.

Because the West Side bike path is pretty heavily trafficked any time after 7:30am and because the terrain is flat and forgiving, a lot of cyclists refer to these miles getting out of the city as “junk miles.”

As early as pancake flat Mile 6, where I ride by Chelsea Piers, I was having trouble keeping up my usual pace. I was winded, sweaty, lethargic. I felt awful. I was 15 to 20 minutes late to meet Terry even though I left on time. I hadn’t slept well the night before and was riding on less than five hours of rest. At first I chalked up my exhaustion to that and to the humidity. I stopped with Terry for a few minutes to catch my breath, cool off, and drink some Gatorade, and then we rolled out again.

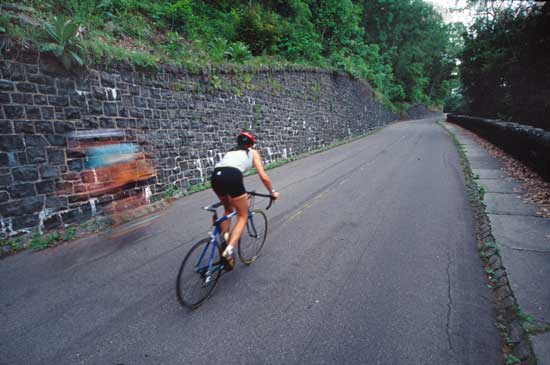

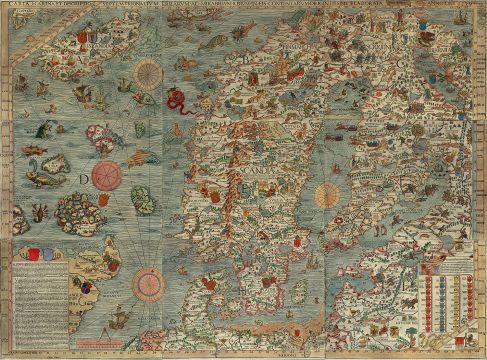

The eight-mile stretch of road through Palisades Park, also known as River Road, is popular with cyclists because it’s scenic and beautiful, trafficked by few cars, and it offers enough hills along the way to be excellent training for athletic goals and events of all kinds. Two of those hills are generally regarded as the most challenging: Dyckman Hill, which is moderate enough in duration but is still the first incline that’s visibly steep enough to make me take a deep breath if I haven’t been on my bike in a while, and Alpine Hill, which is a mile-long climb at the northern end of the park. Alpine is a little like the Magic 8-ball of hills. It can kick my ass on a tough day, it can still feel arduous even on a decent day, and it’s also the hill where it shows if I’ve been putting in a lot of time and am starting to make notable progress.

A cyclist going up Dyckman Hill Road, Palisades Park, New Jersey.

Dyckman Hill felt like Alpine Hill to me. I was able to pull myself up, but I sagged the whole way. Inside, I felt like my body was creaking. I stared at my odometer the whole time to keep myself from focusing on the remaining distance up the hill. It didn’t register in my head until later on that my speed uphill was a solid half-mile to full mile slower than usual. This summer, Terry has been in the best shape he’s been in since we met. He zipped his way up the hill. I didn’t try to catch him. My chest felt tighter than it had before. It occurred to me that the chest tightness from the previous week had never fully left me at all.

Alpine Hill was harder still. Terry was out of eyeshot quickly. Knowing I’d meet him up at the park rangers station where we usually stop for water and a bathroom run, I let him go. I cranked up at my own meager pace, frustrated, pedal rotation after pedal rotation. A few other cyclists passed me going up, but soon enough, I was too tired to care. I just wanted to make it without stopping. I cycled up Alpine the first time in 1999, and I’ve done it with regularity since 2006 or 2007; in my worst shape, without training, riding on a mountain bike that might as well have been made out of cast iron, I’ve never stopped mid-hill.

The view from near the crest of Alpine Approach Road, Palisades Park, New Jersey, July 2012.

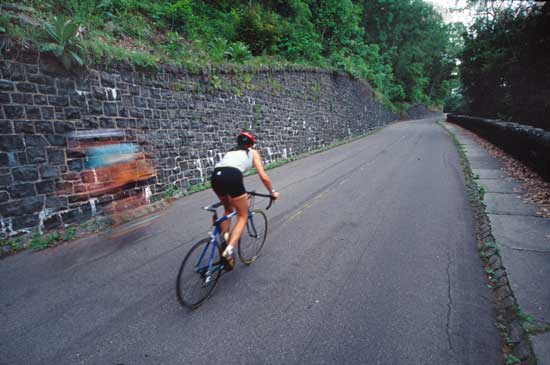

I had brought a camera with me to take some photos along the road for this blog. The last hiccup of the Alpine Hill incline has a bend in it, so I stopped just shy of that and turned around so I could get some clear shots of the rise of the hill grade and of a few cyclists pedaling up it. As soon as I heard the shutter click on the last photo, a wave of dizziness, sweats, and nausea rolled over me. I almost thought I was going to pass out. I leaned over my bike frame and waited until it passed, but I was shaken by it, literally and emotionally. Something wasn’t right.

Another view of Alpine Approach, Palisades Park, July 2012. I took this photo right after I cycled up the hill myself, and I almost passed out right after hearing the shutter on my camera click.

Someone who isn’t me might have turned around after that and gone home. But I was 24 miles from home, at least 10 miles from any decent public transportation, and I was hungry. It made more sense to continue to Nyack, get something to eat, take whatever rest I needed, and then make my way home as slowly as I needed to. That’s what I did. Nothing remarkable happened except that I was now afraid. Even on a strong day, the five miles between Piermont and Alpine, headed south to go home, are the hardest for me out of the whole 70-mile trip. The road out of Piermont is a series of climbs of varying length and grade, one after the other; perhaps because of their back-to-back succession, as well as their appearance more than halfway through the route, they all seem more difficult than any of the hills in Palisades Park. So my only goal was to take my time and make it home safely.

My friend and one of my training partners, Terry Christopher, kicking back at one of the outdoor tables at the Strictly Bicycles bike shop. Don’t let the easygoing look he has fool you. He is a fierce rider. About two minutes after I snapped this, the sky opened up, and it poured so hard, we huddled together under the table umbrella.

I did it, but it felt the same as the first 35 miles had. Like the cycling equivalent to a root canal. The sun burned off the cloud cover on the way back. By the time we got back to the GW Bridge area, it was sweltering so we stopped at the bike shop near the bridge for water and to cool off. At that point I didn’t care what time it was, or how slow I was going; I wanted to rest. Terry and I chatted and caught up. He made me promise to call the doctor first thing on Monday. I didn’t argue with him. We sat long enough for a storm to sweep in, and it poured and poured, hard enough that we waited until it lightened before we headed out again.

In an email exchange later that same day with my brother, he pointed out that any number of environmental factors could be causfor of the symptoms I was having, too: the heat, the humidity, old air filters in the air conditioners, high pollen count, dust and detritus from the building construction site down the block.

Terry, ever loyal, sent me messages in the two days that followed, as he promised he would, imploring me to make sure I made an appointment and kept it. I went to the doctor that Tuesday. She checked me out, had me blow into a spirometer, asked questions.

The semi-likely verdict: mild exercise-induced asthma. She gave me the choice between coming in for more pulmonary testing to narrow the possible causes or trying an albuterol inhaler before exercising. She said that asthma was the most likely cause because my symptoms were intermittent and only really showing up during exercise, with bouts in between during which I felt fine. “If it was anything more serious, it would be more constant and it would be progressive,” she said, “getting worse the longer it went untreated.” She told me the inhaler wouldn’t hurt me, and if it didn’t help, I could still come back in for more testing. I got the prescription filled the same day.

My new albuterol inhaler.

I’ve used the albuterol inhaler every weekend since then, before each of my long rides. It’s a simple enough device and yet the detailed instructions and diagrams seem worthy of a Master’s Degree. Nothing on them says what I’m supposed to do about the fact that, as I try, per the instructions, to coordinate simultaneously depressing the canister on the inhaler, sealing my lips over the mouthpiece, and breathing in deeply, fully, and quickly, my tongue gets in the way. In the 20 seconds that the two inhales of magic medicine take, I am overcome by the nagging feeling I often get when I do my own taxes or fill out bureaucratic forms at work: that I’m doing it wrong. Still, whatever level of albuterol is making it into my system, it seems to help. For which I’m grateful.

Of course, I’m still slower than I’ve been in past years. I’m just no longer dizzy and winded. I try to keep in mind that all the other factors—exhaustion, weather, inadequate training time—are still influencing my performance. It’s occurred to me that these symptoms may have been with me for longer than I realized. My lungs feel more expansive, which is great, but it also means that I notice the effects of my broken nose more. I’ve broken my nose multiple times, and the result is that my nasal passages are stuffed up most of the time. It never mattered much until I started getting more serious about athletic pursuits. I’ve had a referral to finally get my nose fixed since last December. It’s time to make the call.

I know how lucky I am that the physical health obstacles I’m encountering are minor and manageable. Everything I’m experiencing is treatable. It’s not even close to a small glimpse of what it must be like to wake up each day with a genuine, progressive illness, not knowing whether today is a day when your own body is going to betray you.

I’m also aware that the timing of all this means I need to recalibrate my own expectations for the actual Braking the Cycle Ride in September. At some point during the past month, Jen observed to me, gently, “You know, you might not have the ride you want to have this year.”

The first time I did Braking the Ride in 2008, I trained like hell from April onward, but I still went into the event terrified that I wouldn’t be able to ride every mile. Completion was my only goal. I was more shocked than anyone that as hard as the ride was, I could do it. The second year I signed up to do the ride, I experienced some injuries partway through the summer, and it also rained torrentially all season; I wasn’t sure what to think going into the ride itself, but again, I surprised myself by exceeding my expectations. Not only did I finish, I rode strong and fast, faster than I ever thought possible. That was a big deal because I think I needed to prove to myself that the first year I rode wasn’t a fluke. My third year, I knew I could complete the ride, and I trained less than in previous years, but I still put in a lot of bike time and miles. As always, I was nervous going in—a lot can happen in 300 miles, after all. The obstacles were different from previous years; I had a futzy stomach the whole ride, and the heat got to me and slowed me down. I still rode every mile, though.

Jen wasn’t trying to tell me not to ride or to give up or to stop training. She was trying to get me to come to terms with the possibility that I might bump up against my limitations in a new way this year.

My partner Jen, who is my biggest cheerleader in all things. This photo was taken during Braking the Cycle 2010, on Day 3, Mile 250 or so; Jen was on the volunteer crew. What a huge pleasure it was to ride into a rest stop and be able to see her smiling face. She’s crewing again this year. Lucky me. Photo by Alan Barnett.

Because I know Jen is right, I had a useful chat with my friend and rider coach Blake about the season I’ve been having. Blake Strasser is an athlete extraordinaire. She’s done the New York City Triathlon, the NYC marathon, more long-distance cycling events than I can count. She’s a two-time Ironman finisher. An Ironman is the pinnacle of triathlons: It’s a 2.4-mile swim, followed by a 112-mile bike ride, followed by a full marathon run (yes, that’s 26.2 miles), done in that sequence, without a break. Blake has been a hardcore, disciplined athlete for a long time, so I figured she’d also run into her share of challenges along the way.

I told Blake I was nowhere near where I’d like to be or where I’ve been in the past, that the riding has been harder, physically, than it’s been any other season. I know this comes with the territory sometimes, but it’s frustrating. So I asked her, “How do you deal with it psychologically when, for whatever reasons, you have a tough season?”

Superhero Blake Strasser, my friend and the Braking the Cycle rider coach, who convinced me to sign up for my first Braking the Cycle ride in 2008. At the time, I knew no one on the ride and had never attempted anything this physically ambitious. Blake is a hero of a human being and a kick-ass athlete to boot. I am posting this photo from BTC 2011 partly in the hopes that she will wear this outfit again during this year’s ride. If you are a marathoner and two-time Ironman finisher, you too can look this h-o-t!

Blake didn’t tell me anything I didn’t know, but it helped to hear it from someone who has attempted and succeeded at events far more arduous than anything I’ve done. The main thing with tough seasons, she said, is to reassess goals and remember why I’m doing it. She also shared that she’s had a lousy training year, too—some big health issues and few smaller things, which led to being under-trained, under-rested, etc.

It all sounded very familiar to me.

“My body is just not responding to training,” Blake said. “I’m getting it done, but not seeing gains. I started the year gunning to finish my Ironman in under 13 hours. Now I’m just going to finish it—be healthy, have some fun, help some people along the way. And enjoy a beautiful route. New plan. Good plan. A not-beating-myself-up plan.”

Blake is one of my heroes. And she and Jen are both right. So it’s time to reassess my reasons for riding.

This reassessment isn’t about giving up. It’s not even really about changing my goals exactly. It’s more about recalibrating how I deal with roadblocks as they arise and the possibility, likelihood even, of not achieving what I’d like. It’s about showing up even when I’m not sure if I can get it done—and showing up anyway. And riding my hardest anyway.

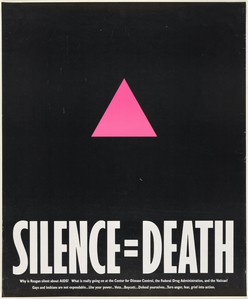

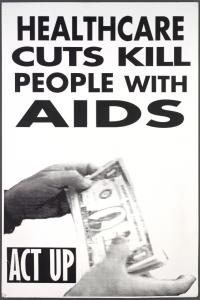

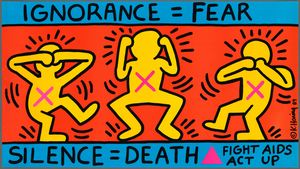

- I ride to raise money that makes a huge difference for a lot of people who get services through Housing Works.

- I ride to raise awareness about a disease that’s been with us for far too long.

- I ride because people with bigger obstacles and challenges ride despite those difficulties. When they can’t ride, they walk. When they can’t do that, they cheer on other riders. They show up, however they are able. That inspires me.

- I ride because I love the compassionate, courageous riders and crew who do this ride.

- I ride because even on my worst day, I love to ride and have a great time.

- I ride because showing up when I’m struggling and feeling weak and trying my hardest to ride strong anyway might be a bigger act of will and grit and even courage than riding when I’m feeling my healthiest.

My literal goals aren’t any different than they’ve been any other year. I am committed to reaching my fundraising target. I have been training and will continue to train every week. I will put in a 100-miler while I’m on Cape Cod next week. On the Braking the Cycle ride itself, I remain committed to riding healthy and strong, having fun with my friends along the way, and doing my best to complete every mile. Along the way, I will have to trust my body, my self, my training, the support of all the folks on the ride and on the road.

The rest isn’t up to me. That’s always been true. But in all my years of doing this, this might be the first time that I’ve fully acknowledged my lack of control over the outcome of all the efforts involved. It also might be the first time that is okay with me.

Past Braking the Cycle rides for me were about testing the waters in terms of my own fear, my determination, and largely, my own expanding sense of my physical capabilities. This ride is about those things, too, but the real challenge is about acceptance of and surrender to the many things that are out of my hands and still being willing to be present and curious about what I can do.

I’ve got a month left to fundraise and train. And then: Who knows what will happen? Not me. But I’m looking forward to finding out…